No Real Winners in the Klamath Basin

For those of you who are not familiar with the area, the Klamath River is about 250 miles long, and stretches from southern Oregon and on into northern California. For years, this area has been in extreme distress as all those who depend upon it for its water are scrambling to decide how best to address this crisis. Farmers, Klamath Tribes members, conservationists, and many others are fighting to preserve the basin, but not everyone can agree on what issue takes priority.

To describe the area, many have called it a “sort of upside down river basin.” The area is fairly shallow, slow moving, and warm, and the river gets progressively wider as it makes its way towards the coast. There are some issues in the upper basin with nutrient loading, mostly phosphorus, which leads to large algae outbreaks in Upper Klamath Lake, thus seriously degrading the quality of the water. That water is then fed into the Klamath river, the algae warms the water even further, and the consequences spread to everyone downstream.

In addition to those who use the water for crop and animal agriculture, numerous indigenous tribes have called the basin their home for centuries. They depend on their ability to fish the river, and they also traditionally hunt birds and game and gather plants, which are all dependent on the water from the Klamath River. With the environment in Upper Klamath river producing less water, and with the demands from the Klamath Irrigation project, you continue to have more demand with an ever decreasing supply.

In an attempt to address some of these issues, the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement was created in 2015, but was never enacted, largely because the agreement included the removal of the dam. To many in the area, this idea was too radical. Complicating things further is the Klamath Tribe’s senior water rights. Their goal is to reserve enough water to save the endangered fish. While I don’t think anyone would think saving species of fish is bad, it does mean there’s less water to go around, and that makes it hard for local farmers to irrigate their crops. The Klamath Tribes began advocating in 2001 for dam removal. After more than two decades, they did succeed, and the dams, some of which were build before the Environmental Protection Agency regulations even existed, are scheduled from removal in 2023.

To put it mildly, its a mess. Even worse, this mess has been going on since the 1970s, when the Klamath Tribes were told it was illegal for them to harvest salmon as they always have. This era is known as the Fish Wars, as tribal members fished anyway, and police, SWAT, and National Guard forces cracked down on the tribal members, sometimes with brutal force. Don’t worry. It gets worse.

In the early 2000s, when the basin was suffering from yet another drought, the Federal Bureau of Reclamation, the agency that helps govern water management in the West, decided to shut off irrigation to 170,000 areas of farmland. The fish were saved, but as you might imagine, farmers were not pleased. After a dramatic political dispute (I mean, what political dispute isn’t dramatic, but I digress.), the George W. Bush administration reversed the figurative tides, and turned the irrigation water back on. As a result, the area experienced the largest fish kill in the history of the United States.

Now, there are hopes that the damn removal will provide positive results, but the irrigation issues are likely to remain contentious as droughts continue to deplete the already scarce water resources. Right now, the only way to approach resolving any issue is for one side to go to court, sue, and then the courts decide who wins and loses a seemingly endless battle that ensues between those need the irrigation for their crops, and those working to protect the fish living in the lake and river. In fact, the Klamath Tribes are currently suing the Biden administration. Additionally, there’s a lot of debate about whether or not the water quality or the water quantity is killing the fish. In the end, there seems to be no balance. Hannah Gosnell, a professor at Oregon State University, has been studying the water conflict in the Klamath Basin for 15 years. She believes that as difficult as it may be to accept, it won’t be sustainable to keep up historic levels of irrigation.

Some tribal decedents that also farm the area believe there is a way to fix this, but for now, the conflict rages on. Now, as an animal agriculture advocate and farmer in Oregon, I do want what is best for the basin, but it’s important to me to have data to analyze.

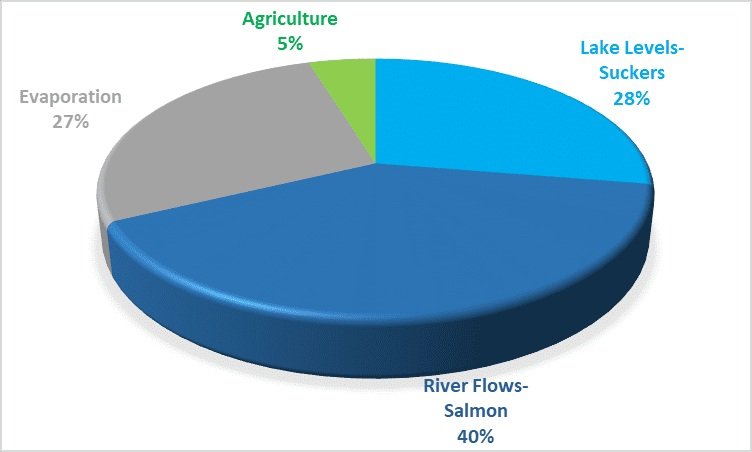

I don’t have all the right answers, and I certainly am not interested in harming an ecosystem, but I do think it’s important the interest of agriculture be seriously considered in attempt to find solutions. It’s by far the smallest usage of the water. While agriculture does evolve and become more efficient through technology, even eliminating it altogether will not save the Klamath Basin.